by Wardah Kamran

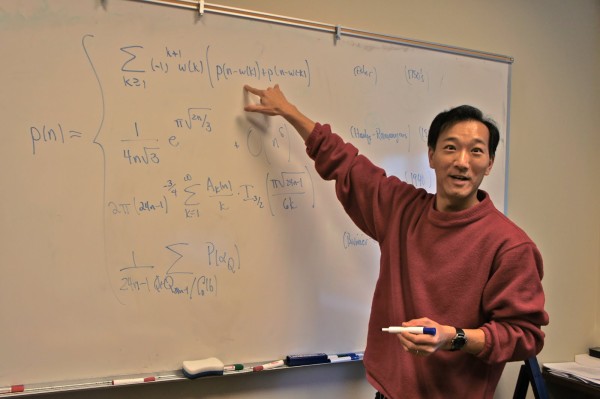

Ken Ono wears many hats. He is the Stem Advisor to the Provost and the Marvin Rosenblum Professor of Mathematics. He also has an affiliate appointment in Statistics and is a Courtesy Professor of Data Science and Electrical and Computer Engineering.

Despite his titles, Ono defies characterization. A true Renaissance man, he cannot be put in a box. When he is not making breakthroughs in number theory, he is hosting the “Hoos in STEM” podcast and helping UVA’s Olympic-caliber swimmers track their performance. Outside of UVA, Ono is testing the mathematical abilities of AGI with the makers of ChatGPT.

Ono energetically pursues advancements in his work and has a strong sense of direction. However, this wasn’t always the case. With a unique start to his career, it took Ono some time to get to where he is now.

"I really don't care about grades. I recognize that they are necessary, but truly being passionate about a subject is what matters."

An Atypical Beginning

Ono’s parents grew up in post-World War II Japan. When the Allies were rebuilding the country, Ono’s father was taught by mathematicians sponsored by the National Science Foundation. He later moved to the U.S. to build his career in the Western world.

“That might sound like a Cinderella story, but it is not. My parents moved to a country, into neighborhoods, where everyone hated them because they came from the country that bombed Pearl Harbor,” Ono said.

At work, Ono’s father was revered for his talent in mathematics. At home, it was quite different. Ono’s parents experienced horrific acts of racism because of their Japanese heritage.

“My parents had come to the conclusion that the only way the Ono boys could succeed would be through schoolwork because that's how they succeeded. Otherwise, there would be no room for us in this country,” Ono said.

Ono attributes his early mathematical genius to his father. But just because Ono was gifted at something, didn’t mean he liked it. At least, not just yet.

“In the early 1980s, I hated math and wanted to run away from home. And I did. I dropped out of high school. I really shouldn't be alive today,” Ono said.

When he was younger, Ono envied how other children played and relaxed while he took the SAT and learned geometric functions. Ono didn’t want to do math, he wanted to have fun.

“The pressure was horrible, and it would take me until my early 40s to understand that [my parents] were doing what was best for me,” Ono said.

In Ono’s office hangs a letter from the wife of Indian mathematician Ramanujan. In 1984, the letter arrived at Ono’s house, leaving his father in tears. This is when Ono first heard about the story of Ramanujan.

“The first thing I heard was ‘Oh, he was a high school dropout. He was a two-time college dropout.’ And that gave me hope. It was the first time from my parents that I heard it wasn't the mindless pursuit of grades that mattered. That there could be someone in an academic field who was a hero to my parents, but for reasons other than ‘that guy got into Harvard or that person got an 800.’

It was really for the quality of their story and the meaningfulness of their achievements,” Ono said.

Eventually, Ono took part in the Center for Talented Youth at Johns Hopkins University. There, psychologist Julian Stanley took an interest in him. Though Ono did not have a high school diploma, Stanley was able to convince the University of Chicago to admit him as an undergraduate student.

Initially, attending the University of Chicago was Ono’s way of getting away from the expectations of his parents. However, he ended up finding some professors who built on the story of Ramanujan and showed him the beauty of mathematics. While this experience didn’t completely sell Ono on the concept of mathematics as a career, it did push him to continue on to graduate school.

“I graduated from the University of Chicago with a 2.7, which is horrible. But I had some professors that really took a chance on me. I went to UCLA for graduate school, honestly not thinking I was ever gonna get a Ph.D. It was just, like, get away from home. It'll buy me a couple of years with a TAship so I can figure out what I really wanna do with my life. And that's where I met Professor Basil Gordon,” Ono said.

Ono was inspired by Professor Gordon and his approach to math as a work of art rather than a means to an end. And, as fate would have it, a book about Ramanujan’s life titled “The Man Who Knew Infinity” would also come out while Ono was in graduate school. When Ono and his Ph.D. advisor read it, they couldn’t help but find the math beautiful.

“What was just a get-out free card has become my professional identity. Through my mentors like Professor Gordon at UCLA, I see universities very differently from how I saw them growing up. I really don't care about grades. I recognize that they are necessary, but truly being passionate about a subject is what matters. Sometimes it's a long way out of your way to travel a short distance properly,” Ono said.

Ono would go on to produce the film “The Man Who Knew Infinity” and star in “The Genius of Srinivasa Ramanujan,” a movie about the impact of Ramanujan’s work. Despite it taking him longer than his parents may have hoped, Ono grew to find both love and joy in the field of mathematics.

“I view my work as fun.

I don't view it as the pursuit of grants or the pursuit of awards. I'm just delighted that people care enough to let the kind of job I have exist,” Ono said.

The Beauty in Mathematics

Like many mathematicians before him, Ono is interested in the study of prime numbers.

“The study of prime numbers has a very long history. It's basically the first topic that ever came up in mathematics after people learned how to count. The Greeks were studying the primes, and some of the simplest questions you might ask, we don't have the foggiest idea about,” Ono said.

Primes are numbers that are only divisible by one and themselves, and there are an infinite number of them. But, as there are many kinds of infinity, there remain questions about how far apart each prime lies from the next and how to predict primes without the long process of dividing.

Ono, his former graduate student William Craig and Jan-Willem van Ittersum published a paper in 2024 titled “Integer partitions detect the primes.” This paper was a finalist for the 2024 Cozzarelli Prize in Physical and Mathematical Sciences.

“What we have done in our PNAS paper is we've constructed infinitely many completely new equations whose solutions are exactly the prime numbers. And what's important about that is none of these equations rely on trial division,” Ono said.

In modern cryptography, prime numbers are used to secure online communications. Ono’s work with primes doesn't affect the reliability of current systems but may have future implications.

“As a number theorist, I want to answer questions about the primes. It's a question of art. Will these theorems be useful in applications later?

I fully expect it,” Ono said.

Mathematics in Real-Time

For most of his career, Ono was motivated by questions that spoke to only experts in his field. While this led to a fruitful exploration of mathematics, Ono struggled to explain to others why any of his theoretical frameworks mattered. This was until he started working with swimmers and sensors, something he considers his most fun work.

“[Conceptual] mathematics speaks to me as a beautiful theoretical question that may have implications for the future. The work that I do with these sensors is put to good use in real-time,” Ono said.

As an amateur triathlete in his 40s, Ono grew frustrated when the swimming coach he hired wasn’t giving him specific advice. Then, when he was a Professor at Emory University, he had a thesis student named Andrew Wilson who wanted to compete in Division III swimming but didn’t know how to improve.

It wasn’t until Ono went to Oslo and spoke with Norwegian mathematicians that he discovered the use of technology in sports. The Norwegian mathematicians revealed to Ono that they used science to help their Olympic athletes improve their pole placement in ski racing. This gave Ono an idea.

When he returned to Emory University, Ono told Wilson about what he had discovered and they immediately went to work. Putting sensors on Wilson, Ono tracked his movements in the pool and looked at the data to see where performance could be enhanced.

“People are thinking very hard about how to make fast skis. They’re thinking very hard about diets. But, believe it or not, they're not thinking as hard about biomechanics now that we have all this technology available to us,” Ono said.

Rather than telling Wilson to emulate famous swimmers like Michael Phelps, Ono offered tailored feedback to help Wilson improve rapidly.

“Andrew Wilson went from not being able to make the traveling team in Division III to Olympic gold in Tokyo 2020. When he won the pro-national championships for the first time, he started getting a whole lot of calls [asking]

‘What are you guys doing at Emory?'” Ono said.

When Ono arrived at UVA in 2019, he started working with UVA’s swimmers. Since 2021, the UVA swim team has set 83 American records. They also won 25 of the 39 medals for the U.S. during the last world championships in December.

Ono is happy to continue his work with sensors at UVA. Specifically, Ono appreciates being able to find immediate uses for mathematics through collaboration with different departments.

“Being able to work with engineers, data scientists and statisticians on things that matter almost in real-time — I don't wanna say that's more important, but it's definitely a different kind of fulfillment that I've never had before coming to the University of Virginia,” Ono said.

"We have people thinking very deeply about implementing AI in their individual research programs. But we are also thinking very deeply about how we train our students for the future so they come out of the University of Virginia with a degree that matters.”

A New Endeavor

Ono is currently working with Epoch AI, a company funded by OpenAI. His team, Frontier Math, is creating large problem sets to test AI on different levels of mathematics.

Though Ono is heavily involved in improving AI, he was initially hesitant when it emerged.

“When ChatGPT came out, there was this knee-jerk reaction, like, ‘Will computers ever replace us? Oh, no, my computer is never gonna be able to prove the theorems that I prove in mathematics,’” Ono said.

However, Ono now no longer underestimates the power of AI. While AI still makes simple mistakes, the errors are becoming rare. Ono considers decreasing these flaws his most important work.

“We are at a point where we need to teach AI to check its own work, know when it's made a mistake and pivot to a different kind of question.

Two years ago, I thought [AI was] just the accumulation of human knowledge. That there was nothing that represents something that looks like human thought. No. We are there now,” Ono said.

Currently, AI can pass oral qualifying exams at the Ph.D. level at institutions like Princeton University. Despite this, Ono is not worried about the future of education.

“Don't be afraid here at the University of Virginia. We're thinking very deeply about future-proofing our education, which is a challenge because these abilities are developing at a rapid rate. Here, we're very good about it. We have people thinking very deeply about the ethics of AI, as we should. We have people thinking very deeply about implementing AI in their individual research programs. But we are also thinking very deeply about how we train our students for the future so they come out of the University of Virginia with a degree that matters,” Ono said.

Ono is currently interested in making AI more human by improving its ability to sense the human world without having to fall back on information it has repeatedly seen.

“People generally like to talk about AI being able to connect with people. I think we all get that. I'm not ignoring that. But I wanna say, as a scientist, [there’s something] even before the being human part means how AI interacts with emotions. I'll give you an example that I think most people can recognize. Why can we see Magic Eye [illusions], but a computer can't be trained on it? How do we teach it? That is a barrier. That is, in my mind, what is truly being human in terms of intelligence,” Ono said.

Recently, Ono has been elected as an Honorary Member of the Romanian Academy of Sciences — an academy where foreign memberships are rare and only four members are honored every year across all fields of science.

Ono is excited to continue making advancements in the field of mathematics, as well as continuing to try the boundaries of what science can be. While he already wears many hats, he is not afraid to try on a few more.